Surveillance For Me, But Not For Thee

I adore information. I know it’s a bit like saying “I like water.” However, I enjoy delving into how information is crafted and exploring how we do or do not understand it. This feels natural as a part-time English speaker: certain words and phrases from one language require context, to be understood in another. I found David Borkenhagen’s essay, The Geometry of Other People, where he uses cognitive semantics to demonstrate how geometry explains human relationships. At its core, cognitive semantics is concerned with the study of meaning in language, arguing that our use of language is shaped by our worldviews—different cultural groups may interpret the same phenomena through varied lenses.

Think about how you use language to navigate the world. Just as some people are naturally better navigators, shaped by their unique experiences and environments, our linguistic abilities and understanding are also shaped by our individual life journeys. As another essay suggests, good navigators are mostly made, not born—a principle that applies to our mastery of language and communication as well.

Why am I telling you this? Because it’s dawned on me that when cognitive semantics intersects with power, something happens: people say one thing, and mean another.

Check out this New York Times article from August 17, 1858:

"Superficial, sudden, unsifted, too fast for the truth, must be all telegraphic intelligence. Does it not render the popular mind too fast for the truth? Ten days bring us the mails from Europe. What need is there for the scraps of news in ten minutes? How trivial and paltry is the telegraphic column?"

This passage appeared in The Times three days after a landmark achievement in communication technology: the successful testing of an undersea cable that enabled messages to be sent between North America and Europe in minutes instead of days.

Tools to (mis)inform

It appears that the Times writers of that era understood that rapid communication across great distances could undermine the careful management and distribution of information, particularly in wartime.

During the Civil War, President Lincoln established the US Military Telegraph Corps under the War Department to handle strategic communication and manage the flow of information to the public. Recognizing the telegraph's revolutionary impact on information dissemination, Lincoln spent more time in the telegraph office than anywhere else except the White House. This new technology proved transformative, especially when used to control the narrative.

Lincoln's Secretary of War, Edwin M. Stanton, took full advantage of this new communication tool. Upon his appointment, Stanton sought extensive powers to oversee the telegraph lines, ensuring all wartime communications, including journalistic, governmental, and personal, passed through his office. This allowed Stanton to control the flow of information, utilizing censorship, intimidation, and even the arrest of reporters to manage public perception. The telegraph office became the nexus of war information, with Lincoln frequently visiting to receive the latest updates.

Stanton's efforts to control the press were intense and often draconian. He appointed an assistant secretary to manage both press relations and the newly formed secret police, leading to the arrest of numerous journalists on dubious charges. The House Judiciary Committee eventually questioned the administration's telegraphic censorship, calling for restraint, but the impact on press freedom was significant during the war.

It is astonishing that, in our current age of "move fast and break things," many accept the desire to outright ban TikTok. Just as the telegraph was a game-changer in Lincoln's time, TikTok serves as a critical modern communication tool. Unlike the transient wartime restrictions of the past, this ban reveals a concerning eagerness to restrict a platform that facilitates democratic information sharing, raising significant questions about the underlying motives and potential impacts of this move.

This ban is not happening due to explicit evidence of meddling in U.S. elections, selling people’s data without their consent, promoting hate speech with addictive algorithms, harming children's mental health, aiding domestic and foreign government surveillance, facilitating hate speech in genocide, or stifling competition by acquiring competitors. TikTok is facing a ban for national security reasons. Oh, wait. Now it’s because of a losing PR game and young people not knowing better about the Middle East, as Mitt Romney and Hillary Clinton said. Which is it?

Why would they say that? Well if language is shaped by our worldviews, then something has happened contrary to their views, right?

In truth: dominant narratives about genocide in Gaza have escaped control, propelled by an app that's moved fast and broken things. This selective scrutiny of TikTok rather than Facebook proclaims that the ban is motivated more by political and economic interests than by genuine concerns for user safety or data privacy. This should outrage members of American civil society who are dedicated to regulating technology, as it flies in the face of everything they've been working towards.

The American Revolutionary Information War

I was being screened at customs in January, when I overheard another traveler in the neighboring booth who had made some sort of illogical journey from New York to Boston. TikTok was their travel guide, they confessed to a border agent.

There’s no question that social media has become pivotal in shaping our worldview. Gone are the homes that routinely watch the 6pm nightly news. This is both a gift and curse, where systems engineered to captivate our attention often do so by appealing to our most intense emotions—both positive and negative. Such designs were crafted in America, not in China. If we truly valued the welfare of our users, especially the young, we would urgently dismantle these mechanisms that fuel a dopamine-driven frenzy, stripping us of our shared humanity. Anything less suggests we are prioritizing different agendas, not the national well-being.

Where were you on February 24, 2022? Other than glued to your phone. I was in the White Mountains—contending with the volume of information directly wired to my dopamine receptors, wondering: why does war feel different, this time?

The so-called "TikTok War" ushered by the Russian invasion of Ukraine has rewritten the annals of how wars are witnessed and woven into the collective consciousness. Unlike the telegraph, where news arrived as disjointed echoes of distant sorrows, TikTok delivers the unfolding saga of human strife with unmediated immediacy, pouring the raw, unscripted realities of war directly into the wellsprings of our perception. When oppression surfaces rapidly, it bypasses the filters of narrative manipulation.

This does more than merely hasten the dispatch of information; it deeply humanizes the theater of conflict. Through the lens of TikTok, the world witnesses the Ukrainian plight not as abstract bulletins but as palpable, piercing narratives of resilience and suffering. The same is happening in Gaza. This intimate portrayal arrives on waves of real-time footage, marshaling a groundswell of support that transcends borders. No wonder there was a mass exodus of Russian nationals. No wonder we don’t believe Joe Biden.

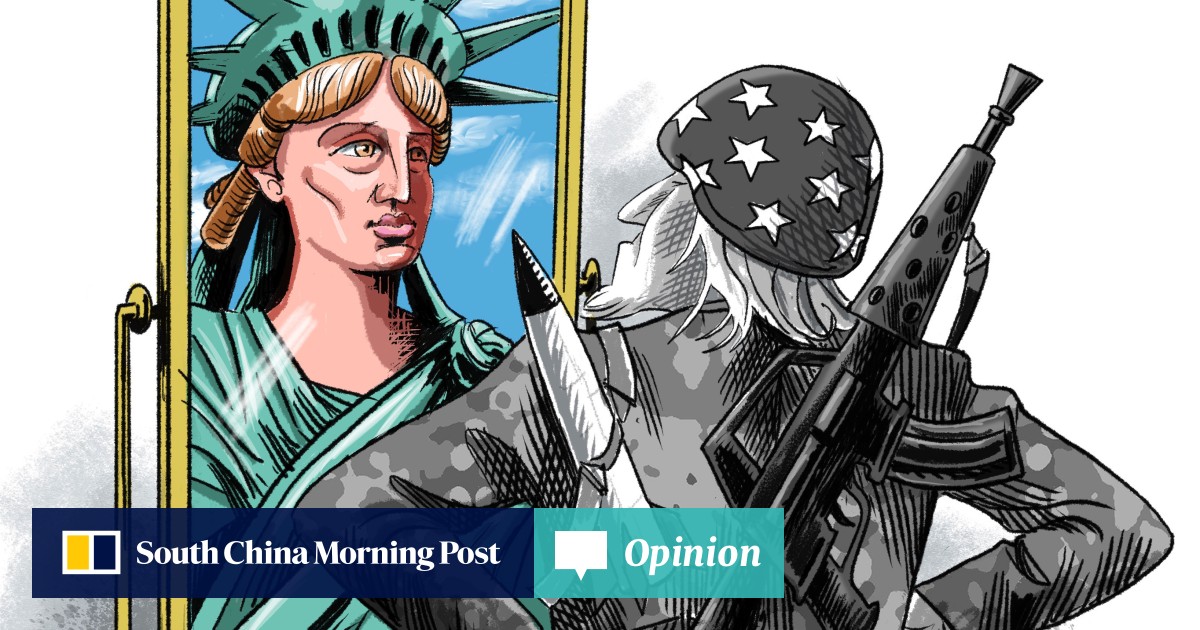

Look to Hong Kong's newspaper of record, The South China Morning Post, for this opinion that points out that Lady Liberty's own duplicitous narratives have reached a boiling point. Archive.is link.

Where the many and the mighty alike can broadcast their truths, there emerges a grand stage for dominant national narratives. The United States, in its historical ballet of liberty and leadership, finds now as it has done in the past, the perennial 'other' in Russia, a foil against which to cast its narrative of freedom. That is not without merit, as Russian fascism is undoubtedly a grave threat. In contrast, America sees a reflection of her ideals and strategies in Israel, positioning much of the Middle East as her orientalist 'other.' TikTok serves as a dual lens: it magnifies America's resolute backing of Ukraine, fitting neatly within its global narrative, yet it also casts a revealing light on the duplicity in America's approach to Palestine, uncovering the deep chasms between espoused values and actual policies.

Groundhog day existentialism

We, children of the internet, are elderly compared to the real ‘digital natives,’ the people 29 and younger who constitute about two-thirds of US TikTok users—some ~90 million people. The first President that this group of people ever got to vote for was Donald Trump. Is banning what has become their primary method of interfacing with the digital world a winning electoral strategy? Is it in the national interest?

Consider the challenges they face. Climate change is a looming catastrophe that threatens our future in the most fundamental ways. Housing, once a staple of the American dream, has become increasingly unaffordable for most, while access to essential healthcare and reproductive rights, including abortion, are under constant threat. These young voters have also grown up in an era defined by frequent mass shootings and gun violence, and the persistent issues of police brutality and racial injustice.

Most significantly, their early voting experiences were overshadowed by the COVID-19 pandemic which disrupted our lives but also exposed deep inequalities and inefficiencies within our systems. Each of these issues has been presented to them as an existential threat, one after another, each election cycle reinforcing the urgency to 'vote blue no matter who' to stave off immediate danger. Yet, the promises of resolving these crises post-election seem perpetually unfulfilled.

The continual deferment of genuine problem-solving leaves many feeling disillusioned. Imagine then being a voter in your early twenties, engaged in your second or maybe even your first presidential election cycle. You've been told repeatedly that immediate threats must be prioritized—vote first, sort out the details later. However, as these existential threats multiply and intensify without resolution, it's no surprise that there's a growing desire among these voters for real, substantial change rather than temporary reprieves.

We need to acknowledge their frustration. It's not just about intraparty solidarity or staving off a conservative agenda. It's about seeing real progress on issues that affect their lives and futures. When young voters see the same cycles of crisis and temporary solutions without real change, their disillusionment isn't just understandable—it's justified. As we look to future elections, it’s crucial to not only confront these existential threats but to also make concrete strides in addressing the systemic problems that continue to plague our society.

TikTok has become their outlet to find solidarity in this shared reality. And to them, the Democratic party is conspiring to take this solidarity and political agency away from them.

We Charge Genocide

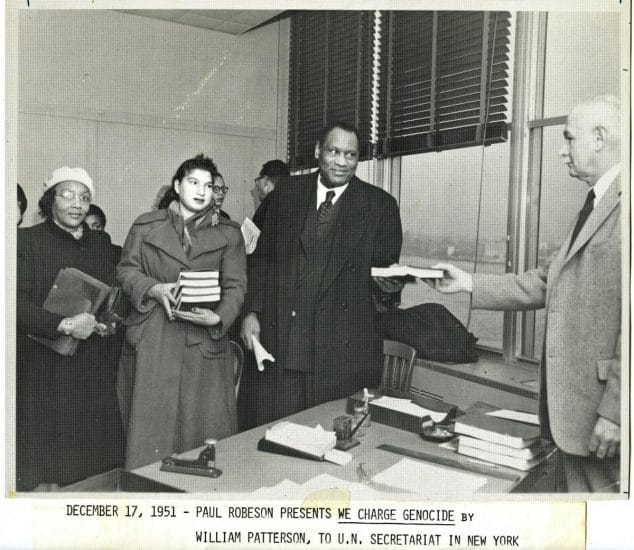

When the United Nations received a petition 73 years ago by William Patterson in Paris and Paul Robeson in New York, W.E.B. Du Bois was among the signatories for both copies. “WE CHARGE GENOCIDE” leveled a grave accusation against the United States: genocide against its Black population.

Crafted just seven years after the term 'genocide' was coined, this 240-page petition was designed to shock and provoke. Its architects aimed to draw a stark parallel between the horrors inflicted by the Nazis upon Jews and the centuries-long brutality endured by African slaves at the hands of their American captors. This was a deliberate and dramatic call for accountability, placing the United States in the harsh light previously focused on Nuremberg's defendants.

Initially, the media's response was tepid, with the petition earning only brief mentions in the press. Now, seven decades later, the document’s significance has magnified against a backdrop of persistent police violence and racial health inequities, especially pronounced throughout the pandemic. “We Charge Genocide” now serves as a critical lens through which we reconsider the definition of genocide and insist on the necessity of condemnation, alongside actionable redress and repair.

TikTok was the dominant conduit through which people under 35 understood the racial justice movement of 2020, in response to the murder of George Floyd. It shaped discourse on what it means to reform, abolish, or support policing. Videos depicted stark scenes: police snipers targeting Black Lives Matter protesters from atop a Minneapolis station, backdrops of tear gas, blaring sirens, and helicopters above protesters, all set to the strains of "This is America" by Donald Glover. TikTok not only broadcast these confrontations but also sparked discussions on policing objectives, all contributing to a solidarity movement that led to the largest demonstrations in U.S. history.

A professor from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem observed in 2020 that these same digital markers were utilized by individuals beyond the U.S. borders to express solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement and link it to specific instances of racism and anti-government sentiments in their own regions. In Israel, for instance, solidarity with BLM coincided with the grievances of Ethiopian Israelis against racial injustice and police aggression. She says that this underscores TikTok's ability to help young individuals tailor a personal political stance while engaging with wider political movements.

It is hardly shocking therefore, that the 18-35 TikTok demographic who only four years prior witnessed their leaders sanction the use of militarized police against Black Americans, would express vehement outrage when those same forces confront peaceful protesters on college campuses. Or children being pulled from rubble. Or images of Gaza completely obliterated. It is entirely expected that this audience, already inclined by algorithms to view content critical of police actions, naturally becomes the viewers of both the unsettling footage posted by some Israelis and the urgent appeals from Palestinians, who have faced tremendous suffering since October 7. This is true regardless of the platform.

But it is TikTok users have been quick to point out political duplicity. One user in particular that I saw showed messages from US politicians in support of student demonstrators in Hong Kong. The same politicians who have been quick to encourage police violence against student demonstrators in America.

If you're not engaged with TikTok and remain doubtful, consider this: simply ask any young person you know—perhaps your own children or those of a friend. You'll find that even kids who aren't old enough to join street protests are making their voices heard in video games. There is a major divide in how different generations receive and comprehend information, and this schism is shaping entirely different worldviews.

"China China China," yes I hear you

I am not diminishing the significant sway TikTok holds over broad swathes of the American populace. I am saying that younger voters remain unconvinced by the national security justification provided by lawmakers, suggesting this debate is less about “left versus right,” or “foreign versus domestic”—it is about young versus old. Acknowledging this does not negate the reality that China, with its expanding technological prowess and strategic global investments, poses a substantial and multifaceted threat to American interests.

China's influence extends beyond simple geopolitical maneuvers; it leverages technology, trade, and economic dependencies to carve a significant space in global power dynamics, challenging American hegemony. The concerns around TikTok, owned by Chinese company ByteDance, are not unfounded as they touch upon broader anxieties about data security and the potential for foreign influence in domains like elections. Sound familiar?

But it is America itself that is taking several contentious steps: pushing for the reauthorization of Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, banning TikTok, and increasing military aid to Israel—a policy that exacerbates the ongoing violence against Palestinians. The youth see right through the invocation of democracy and liberty to justify these actions. Disillusionment grows in the TikTok discussion, which uncovers national security excesses and America's uneven claims of promoting freedom. Casting a vote to ban TikTok under the pretense of national security now seems as ineffective as expecting a vote for Biden to bring substantive change.

Section 702's recent reauthorization casts a particularly long shadow, cloaked in the guise of foreign intelligence gathering yet broadening the U.S. government’s warrantless gaze into Americans' communications. This capability was not only extended but also expanded to include a broader scope of surveillance activities, such as monitoring data flowing through U.S. data centers. This extension, signed into law by President Biden on April 22, 2024, continues to empower the NSA and FBI at a time when public trust in governmental oversight of surveillance practices is notably waning. The youth, informed and mobilized through platforms like TikTok, are challenging these expansions of power, recognizing the implications for personal freedom and privacy in a digitally interconnected world.

I don’t think younger voters are stupid; they understand the severe consequences of a Trump presidency. Young people right now are not thinking about November. They are thinking about pressing issues right now like the urgent need for relief in Gaza, student debt relief, higher minimum wages, and affordable housing. The American majority's struggles are acute. TikTok has become a platform of solidarity and support for this group, transcending its ownership and functioning independently of America's ruling minority.

Whose national interest?

The national security concerns about TikTok often hinge on ambiguous references to the company’s potential connections with the Chinese Communist Party, and their ability to target Americans. Yet, where is the outrage over reports that data from WhatsApp, owned by the American company Meta, might have been used by the Israeli military in targeting Palestinians? Meta has denied these reports, but according to their last available Transparency Report, the government of Israel made 1,088 requests of the company between January and June 2023, with more than half categorized as emergency disclosure requests. Meta produced user data in response to a majority of these requests—78 percent. Interestingly, we don't see the same level of outrage from U.S. politicians about this.

I’m Muslim American, and I often contemplate the roles imposed upon us by those in authority. Must we resign ourselves to remain voiceless? Observing the unprecedented level of engagement and organization among Muslim communities on social media platforms like TikTok, more so than at any point in my thirty years, reveals a profound shift. This surge in activity is a testament to a growing disillusionment with successive American administrations and a deep frustration propelling people toward activism.

I mean come on. Muslim Americans 40 and under have been seeing American interventionism in Middle Eastern countries for half their lives or more. It is Muslim Americans who are often at the nexus of national security debates and are especially adept at discerning the real intentions behind such political decisions. We have family, parents, and loved ones who have lived the consequences of these policies firsthand, so of course more than any other, we understand the gravity of these discussions. How dare Hillary Clinton suggest otherwise? It is profoundly insulting that she and others would imply our perceptions are misguided; such statements are not only offensive but also starkly disconnected from the realities we experience as Muslims in America.

Let's face it: American surveillance policy is explicitly racist, while data policy and business practices are implicitly so. The move to ban TikTok reveals this stark truth, exposing the biases and double standards inherent in these policies. And in targeting it we reveal the deep-seated racism within the broader framework of American data and surveillance practice, emphasizing the urgent need for a more equitable and transparent approach to technology regulation and national security. Advocates, where are you? ◼️