Three Points Between You and Your Vote

It is election day, and Pennsylvania's 19 Electoral College votes could determine who becomes president. The state has swung back and forth — Donald Trump won it in 2016 by 44,292 votes, then Joe Biden took it in 2020 by 80,555. In a state where such small margins decide elections, every vote matters.

When my friend Dr. Dana Calacci tried registering to vote there in August, the state website wouldn't accept her signature photo. As a new resident and Penn State professor of computer science, she found this alarming — if she was having technical difficulties, what about everyone else? In a state of more than 9 million voters and 19 Electoral College votes, even a small technical barrier could block hundreds or thousands of new residents from registering. When elections are decided by tens of thousands of votes, these seemingly minor glitches take on new significance.

Election security and modernization in Pennsylvania

After the 2020 election, Pennsylvania faced intense debate over election fraud. While courts rejected most fraud claims, there were some real cases: a judge and a congressman were convicted of falsifying voter records. These incidents, combined with wider disputes about election integrity, led to stricter voting rules in Pennsylvania.

The state has worked to balance voting access with security. In 2016, Pennsylvania's Department of State launched an online registration system to modernize the process. The system helps organizations run voter registration drives and manage records efficiently. It allows approved organizations to build their own registration software, potentially connecting with systems like NGP VAN for voter outreach. The requirements have evolved between March 2020 and May 2024, reflecting new security and accessibility needs.

New residents faced registration hurdles

Dana's case highlights a common problem: new residents without Pennsylvania driver's licenses must upload signature photos instead. This especially affects people moving to Pennsylvania in fall — college students, recent graduates, and professionals. They have the right to vote but face a time crunch with the October 21 registration deadline for the 2024 election.

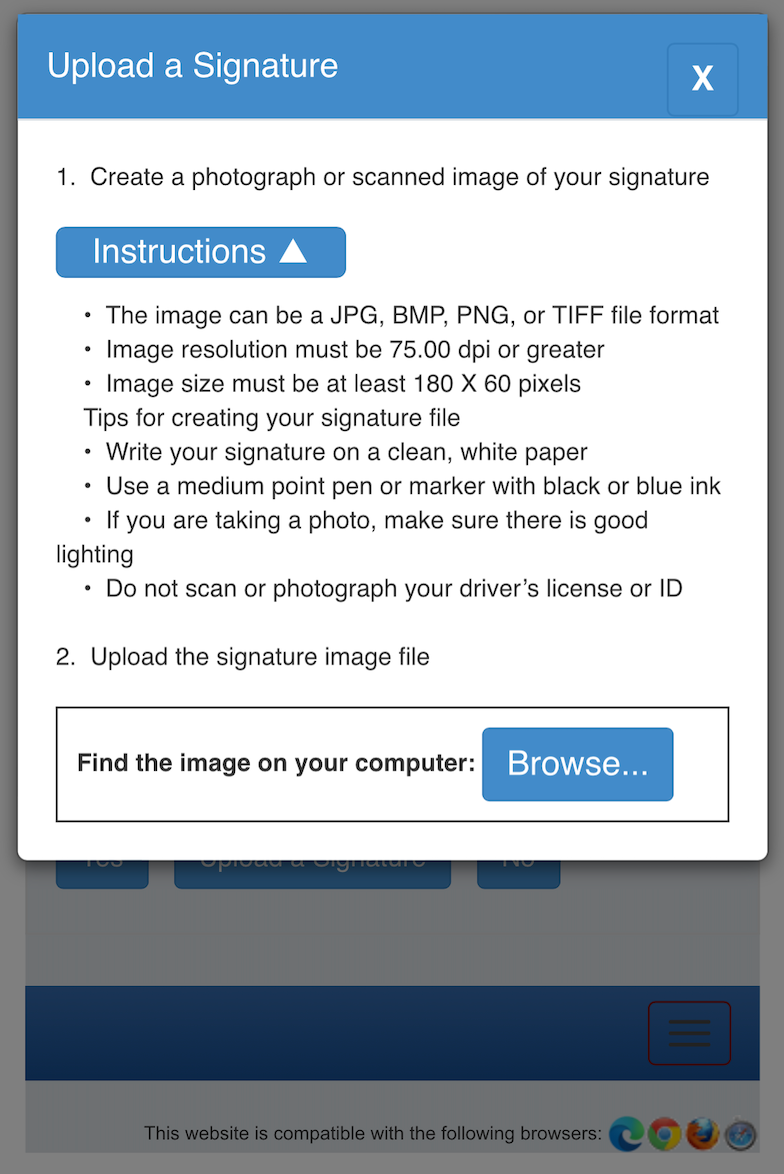

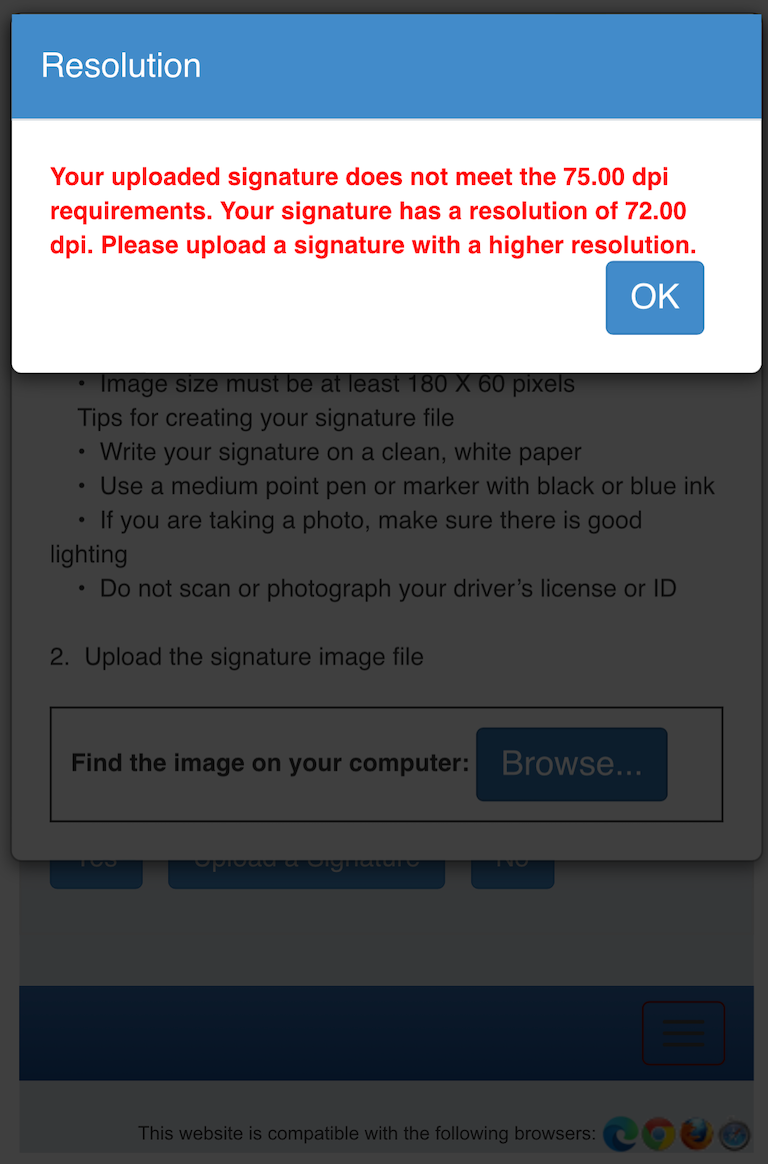

You would think you could just take a phone photo of your signature and submit it. But until recently, the system rejected these photos, claiming the image quality wasn't high enough. This is what Dana sent me:

Pennsylvania's voter registration website in August 2024, showing how it rejects signature photos taken by phone.

The problem was technical but revealing: the system required 75 DPI (dots per inch) — a printing measurement meaningless for digital photos. Most phone cameras use 72 DPI. To register, voters needed to use special software to adjust the photo’s metadata (which is what Dana did) or access a scanner. Both options create unnecessary barriers.

Technology that “just works” is in the public interest

When Dana contacted Pennsylvania officials about this problem, they initially seemed unaware. Yet their own technical documentation showed this was a deliberate requirement. While there are other ways to register, like Vote.PA who would mail you a form for your signature, we shouldn't need workarounds.

Government services like voter registration should be as easy to use as any modern website. If we can shop online with our phones, we should be able to register to vote just as easily. The system should simply check if a signature photo is clear and large enough (by verifying the photos dimensions and file size, for example), not enforce arbitrary technical rules.

Working with the ACLU of Pennsylvania, we got the Pennsylvania Department of State to fix this issue. If you encounter similar problems registering to vote, please contact me.

Why 72 DPI, though?

You might wonder why phones use 72 DPI at all. Turns out that it's a slice of computing history from 1984 when Apple built the original Macintosh. Each pixel on each screen was made to correspond to traditional typography measurements — where 72 points is one inch. This was intentional: it was a bridge between paper and screen, allowing designers to work digitally by employing the same measurements they had used in print.

The screens of today are far superior — smartphones are easily well above 500 pixels-per-inch (PPI), computer displays routinely pass 200 PPI. Yet, like the floppy disk "save" icon that remains in software long after floppy disks have disappeared from our lives, 72 DPI continues to appear in our photo files by default. It's simply a standardized reference point linking our digital today to its paper-based yesterday. The number itself is now arbitrary, which makes Pennsylvania's 75 DPI requirement doubly bizarre — they were rejecting photos of signatures on a three point swing of a dead metric.